Aquaculture: The Good, the Bad and the Restorative

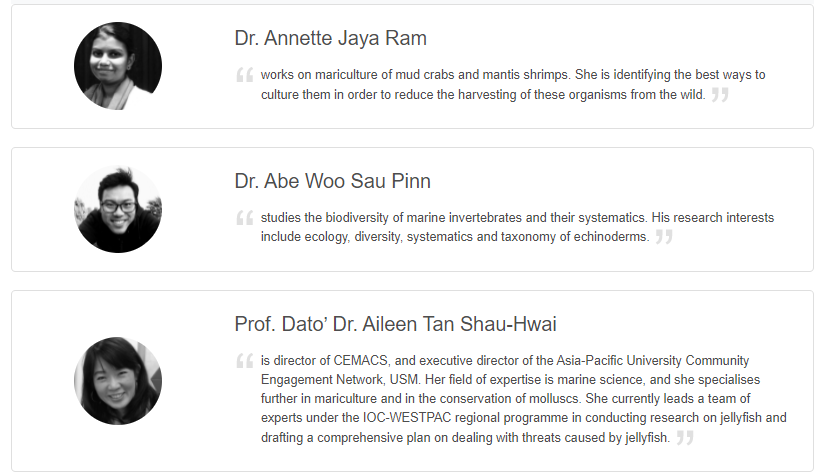

By Dr. Annette Jaya Ram, Dr. Abe Woo Sau Pinn, Prof. Dato’ Dr. Aileen Tan Shau-Hwai

January 2022

CENTRE FOR Marine and Coastal Studies (CEMACS) at Universiti Sains Malaysia is deep in research cultivating bivalves and seaweeds as natural bio-remediators, to reverse the adverse effects of unchecked aquaculture farming.

Penang's aquaculture sector, though a thriving global export industry with significant job creation opportunities, is also a worrying source for severe environmental disruptions. Eutrophication, the result of excessive nutrient loading from uneaten fish food and faecal matter in open-water fish cage farming practices, triggers phytoplankton blooms and increases decaying matter.

Oxygen is consumed during the decomposition process to create hypoxic zones, known also as "dead zones"; this leads to mass cultured fish mortality. The fish farmers of Teluk Bahang had a rude shock in 2019 when they discovered massive fish mortalities in their floating cages. About 50,000 groupers were wiped out at a loss of close to RM800,000. The deaths were from low oxygen levels in the water.

In industrial settings, more import is often given to high production volumes, with little attention paid to environmental factors, and the density of cultured organisms is wholly overlooked. The oxygen level of the waters is interfered with when high densities of fish are cultured in a limited space, exacerbating nutrient loading from excess feed and faecal matter.

Another drawback of aquaculture cultivation is the clearing of mangrove ecosystems to develop fish and shrimp aquaculture cages. Between 2000 and 2012, a study reported an average rate of 0.18% loss of mangrove forests per year in the Southeast Asian region. Locally, several fish farmers gained notoriety for illegally clearing mangroves in Balik Pulau, despite the areas being already gazetted for aquaculture farming.

Restorative Aspects of Aquaculture

This begs the question of how sustainable aquaculture is. Current data trends show aquaculture to have surpassed global marine capture fisheries in meeting the demand for seafood.4 But overexploitation of natural stocks threatens the future of Penang's food security. In this context therefore, sustainability in aquaculture refers to the conscious, cooperative efforts of farmers, researchers and market players in seeking and developing new ways of conserving marine resources, and in protecting the health of Penang's seas for future generations.

Restorative aquaculture, or integrated multitrophic aquaculture (IMTA), something deeply researched by CEMACS, attempts to culture more than one species within the same location to regulate its water quality. Fish, as the target species, is cultured together with additional organisms, whose selection is determined by their ability to contribute to a smaller environmental footprint and to remediate the surrounding waters.

Natural bio-remediators such as mussels, clams, oysters and bivalves are good candidate species to integrate. Bivalves, in particular, help reduce particulate matter from aquafeeds and faecal waste, while balancing the phytoplankton that causes algal blooms and low oxygen levels in the environment. Seaweed, as an extractive species, also uses for growth ammonia and nitrates found in the water, and thus, clears the water bodies of pollutants and phytoplankton blooms to restore the parameters of water quality.

It is estimated that one hectare of restorative farm is able to remove more than a half tonne of nitrogen, by filtering up to 95 million litres of water per day.5 This in turn increases the abundance of wild fish by up to five tonnes per year, and prevents ocean acidification – an effect of climate change – by capturing carbon dioxide in coastal zones.

Countries that have adopted restorative aquaculture approaches are now reaping its benefits, and not just economically. Water quality in such areas has improved and damage to the natural environment minimised. The farming of shellfish and seaweed has also created additional habitats and protected areas for other aquatic organisms such as fish, crustaceans and invertebrates. But for these practices to see success, factors such as the avoidance of low oxygen and excessive nutrient zones, and the types of organisms used for integration in the local environment, must be carefully considered during site selections.

CEMACS hopes to engage and support the community with its research findings to widen the adoption of restorative aquaculture, while unlocking many more health, environmental and economic opportunities.

References

- Richards, D. R. and Friess, D. A. (2016). Rates and drivers of mangrove deforestation in Southeast Asia, 2000-2012. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113(2) 344-349. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1510272113

- FAO (2016). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture. Rome.

- The Nature Conservancy. (2021). Global Principles of Restorative Aquaculture. Arlington, VA. https://www.nature.org/en-us/what-we-do/our-insights/

- Loheswar, R. (2019). Nearly 50,000 fish found dead in Teluk Bahang due to suspected heavy metal contamination. 12 August 2019. https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2019/08/12/nearly-50000-fish-found-dead-in-teluk-bahang-due-to-suspected-heavy-metal-c/1779858

- Mok, O. (2018). Penang exco warns aquaculture operators against illegally clearing mangrove forests. Malay Mail. 11 December 2018. https:// www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2018/12/11/ penang-exco-warns-aquaculture-operators-againstillegally- clearing-mangrove/1702115

Source: Penang Monthly

- Hits: 1239